In a Free Market, Wealth Inequality Is Good for the Poor

How a focus on differences harms the most vulnerable.

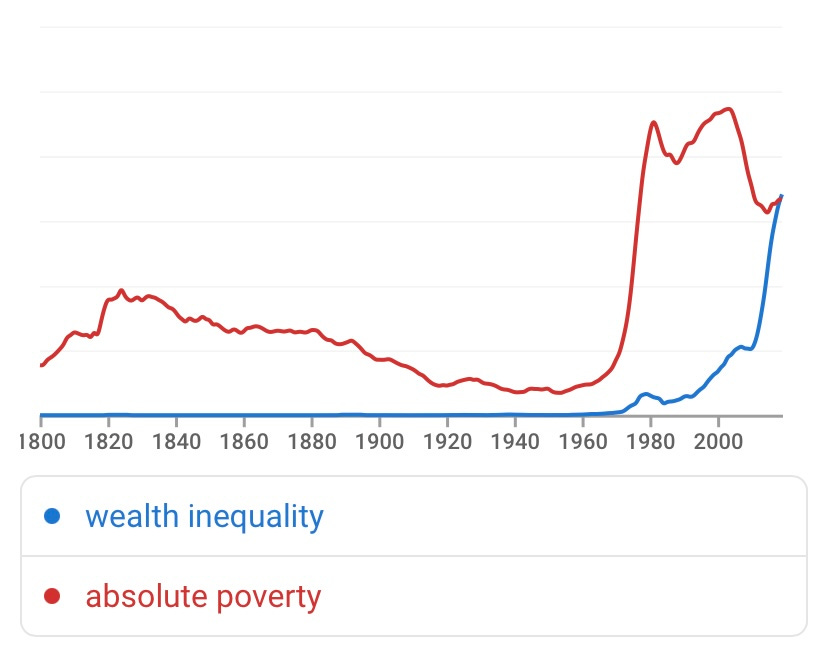

Logically speaking, there is zero necessary connection between the state of the difference between rich and less rich and the state of absolute poverty. There is no link between differentials and quantities to begin with. So I’m left with the question: why is it that for the first time since records began, the term “wealth inequality” has surpassed “absolute poverty” in online and published works? Why is it that instead of fighting scarcity and subsistence face on, 78 percent of Democratic voters decry economic difference and attack those with more in place of aiding those with less?

The logical answer is that inequality and absolute wealth are genuinely connected. That attacking the rich is a rational and effective strategy towards helping the poor. I believe this to be false, as well as a grievous misinterpretation of both the underlying philosophy and resulting psychology of social justice activism. In truth, wealth inequality can be either good or bad for the poor. In a vacuum, it is neither. We’ll start with that indifference and work our way up to how systems similar to our own, with principles of private property and freedom of exchange, turn wealth differences into engines of creation. We will also explore how other such systems, wielding wealth as malevolent weapons of coercion, promote only violence and villainous stasis.

But first, we need to disconnect our understanding of amounts and disparities when it comes to economics. To illustrate, let us imagine a hyper-rich, hyper-advanced civilisation of the deep future. For the sake of world building, let us also assume that this society retains private property and individuals trade freely with one another with mutual consent.

In this world there are citizens many orders of magnitude richer than today: millionaires and billionaires by modern standards; but also planet-owning, system-running trillionaires, quadrillionaires and septillionaires by the hundreds.

Now consider a relatively lower-class multi-millionaire, lounging at his beach-side mansion resort sipping on a cocktail. Or perhaps a relatively middle-class trillionaire, stepping off a hovercraft onto her private archipelago. They both pay their rent to their landlord, the local system’s most successful businessperson and residential planet owner.

Consider the richest and poorest described above. At the lower end of the spectrum, there’s the mansion-lounging, cocktail-sipping ”low-life” enjoying the comforts of perpetual retirement; and at the higher, there’s the enterprising, multi-planetary proprietor busy overseeing the construction of their latest space elevator.

The financial gulf lying between these two characters is vast (really vast). It is more vast, in fact, than that lying between a singular ant holding a single-dollar bill and the entire GDP of the Earth in 2021. But is our luxuriate down-and-out, content in the riches of relative destitution, absolutely poor?

Absolutely not.

The financial differential is, in a vacuum, meaningless. It tells us nothing about the state of poverty of individuals, nor the mechanisms of poverty alleviation of civilisations. It is only when considering specific economic systems that wealth inequality takes on a positive or negative influence.

Association or Serfdom?

I am a firm believer that the average person spends far too little time rejoicing at their lack of medieval peasantry. That is, I should clarify, the average person living in the West or any other affluent area. For others it may not be so different. There’s little to no material disparity, for example, between a modern subsistence farmer living in Vietnam or Bangladesh or Tanzania compared with the average agricultural vassal some 750 years ago. They both work to live (and barely work at that) and they both eat near to all of the produce they create (and barely eat at all). This is not meant to disparage poor farmers who work day in, day out merely to survive; it is meant to illuminate a proposed equivalence between different people living in scarce conditions. But does it really?

Let us consider again two people living under poverty. One is a modern person living in a remote but recently connected area of the world and earning less than $1 per day. The other is a person of the same standing living in, for example, 10th century England. As far as material position goes, they are equal.

In both cases, there exists some wealth disparity. Ours is all too familiar: Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk and Bill Gates (obviously); but also the some 50-ish million millionaires and 50-ish percent middle class global population and 50-plus percent global poor who are richer than this secluded person.

In the 10th century, the disparity is less widespread but just as stark. King Æthelred—Unready as he may have been—was certainly pretty well off. So, again, the two farmers exist in markedly similar situations. Right?

Wrong. The difference lies in the economic contexts to which they owe. 10th century England operated under a feudalist system of economics, within which only a small measure of private property and freedom of exchange existed, and where most lived as subsistence workers indentured to their regional Earl. The Earl was in turn sworn to his King, who was made rich by all manner of economic and military servitude.

In systems like this one, wealth disparities were a means of warfare and tyranny alone. There was little concept of social mobility nor economic development beyond that of noble lords vying at court. The poor in the past stayed poor by design. Riches flowed up, not down. And the powerful maintained their influence at pain of the impoverished.

But what about today? We reliably hear about how the wealthy exploit those poorest in society and how they hoard all their riches with wyvernous greed. This is, simply put, patently false, and could well represent one of the greatest and most cynical conspiracy theories in modern discourse. (Or perhaps, with a pinch of luck, just a simple misunderstanding of the nature of economics.)

Unlike feudalism, systems of private property and free exchange harness wealth disparities as a mechanism of creation. They do so for everyone. Unlike King Æthelred and his flattering Earls, taxing and warring their wealth from within and without their fiefdoms, the modern rich (to the extent that they owe their wealth to the market) are made rich only by making others rich alongside them: through the peaceful and bilateral mechanics of competition and trade.

This can be seen in the case of our modern subsistence worker. Just ask yourself: would you rather be someone earning less than $1 per day in 10th century England, bound and embattled by military rulers intent on prolonging your ruinous servitude; or would you rather be someone of the same income today, newly connected with rich and enthusiastic trading partners keen to engage in collaborative enterprise? There is a reason that over 1 billion people have moved out of extreme poverty since 1990 and not since 990. There is a reason that 20th century South Koreans—not 10th century Anglo-Saxons—went from fettered agricultural poverty to relative global super power in fewer than three generations. They did so through the trade and competition and collaboration afforded by capitalist freedom. They did so without a sword in sight. And they could have only done so much so quickly as a result of the existing wealthy neighbouring nations competing for their business. They became rich because of economic inequality, not in spite of it. And for the betterment of everyone else, to boot.

Alien Nation

To pump our intuitions a little bit further on this, let us again consider a thought experiment.

Imagine if tomorrow an advanced, alien civilisation warped into orbit. Practically overnight, the measure of economic inequality encompassing the Earth would skyrocket. Practically in an instant, we would become like an ant holding a single dollar bill.

But are we better or worse off for this extraterrestrial visit?

Once again, in a vacuum, we are neither. There are broadly three options.

The aliens are somewhat aloof. They sit in orbit and remain cloaked, evading all modern detection methods to enjoy a quiet day out at the zoo.

The aliens are both advanced and benevolent. They visit Earth in a manner that alerts our detection without plunging us into violent chaos. Both diplomatic and economic channels are opened in good faith.

The aliens are evil. They arrive and destroy all known civilisation in a matter of minutes.

It is clear that the effect of our new found wealth inequality is dependent on various external factors. In the first case, the effect is naught. In the second, it is stimulating. And in the third: catastrophic.

And once again, the disparity itself is largely meaningless. The difference between the wealth of the aliens and that of humanity is independent of its effects on us ants and our dollar.

This is not meant to sound glib. Nor is it meant to obfuscate the very real problems faced by the impoverished in the world today. We live in a connected society of very rich and very poor and millions in between. But we have to reason effectively about the nature and mechanisms of what really matters. Is it wealth inequality, or is it poverty? Are they connected, and how?

As it stands, we are getting all these questions horribly wrong. Wealth inequality, on its own, is neither a problem nor an evil. It has zero necessary connection with poverty in economics. But in our current system, it has an overwhelmingly positive impact on those most in need, turning our differences into progress and growth. To the degree that there is inequality, there is opportunity for the poor to trade and excel. To the degree that there is disparity, there is success for all who collaborate in peace.

This is not the case for any other economic system, where zero-sum fallacies stifle creation and work to preserve income divides through force. In such regimes, the measure of the difference between rich and less rich is a measure of the power to maintain destitution. In a free market, it is only a measure of how to destroy it.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing for more undeniably unobjectionable content delivered straight to your inbox. Thanks!

Also, share with your friends and comment below. Criticisms encouraged!

Also also, follow me on Twitter for more optimist shitposts.

> To the degree that there is inequality, there is opportunity for the poor to trade and excel. To the degree that there is disparity, there is success for all who collaborate in peace.

Could you elaborate on this exposition? Are you saying that the more inequality and disparity there is the more opportunity to excel and success by collaboration? This part feels very profound, but I'm slightly confused by it.

Fun read!

> There is a reason that 20th century South Koreans—not 10th century Anglo-Saxons—went from fettered agricultural poverty to relative global super power in less than three generations. They did so through the trade and competition and collaboration afforded by capitalist freedom. They did so without a sword in sight. And they could have only done so much so quickly as a result of the existing wealthy neighbouring nations competing for their business. They became rich because of economic inequality, not in spite of it. And for the betterment of everyone else, to boot.

Could you elaborate on this idea, that economic inequality is a _driver_ of wealth creation under freedom? How so? What's the mechanism? What business of impoverished farmers were South Korea's wealthy neighbours competing for?

Is the idea that, given freedom, opportunities open up other than farming? Or something in that ballpark?