The Enormous Fallacy

“There is a size at which dignity begins,’ he exclaimed; ‘further on there is a size at which grandeur begins; further on there is a size at which solemnity begins; further on, a size at which awfulness begins; further on, a size at which ghastliness begins…”

— Thomas Hardy, Two on a Tower

It is happening again. Another celebrity has declared war on arithmetic. Numbers themselves, it appears, are being weaponised against the wealthy and the planet’s most powerful. Figures like one million, one billion, one trillion… mathematical constructs like power series and orders of magnitude… even the very notion of the sublime itself have become the unlikely bywords in the ongoing crusade against the evils of capitalism. But this obsession with the abstracted figures actually obscures the realities of the physical facts. One million, one billion, one trillion and the rest are meaningless in a vacuum, misleading in analysis, and outright malevolent in the understanding of a moral economics. The numbers, I would like to argue, just don’t add up.

I have written about this before, in Merion West, in an article responding to a Bernie Sanders wealth tax. That piece is behind a paywall, but a drive-by summary of the arguments might look something like:

Billionaires are relatively wealthy but absolutely poor.

There is no limit to how much wealth we can create.

Wealth does not equal money.

Quantifying wealth by numbers is misleading.

Criticising wealth by numbers is harmful.

Capitalism is optimism applied to markets.

We should want more billionaires.

I might also add some complimentary arguments:

Labour theories of value are false.¹

Profit is legitimate and non-exploitative.²

Economics is positive sum.³

¹The classical marginalist critique, that, say, an umbrella is worth more in London than in Lisbon (in rain than in sun), stands as proof that its most meaningful value is conjectured by the consumer—not mechanised by the labourer.

²Subjective theories of value sever the Marxist logic for exploitation. In fact, given the bi-fallible nature of every individual trade, it is equally possible that a worker is getting a higher compensation than the value that they provide to their employer. Workers can, using the same faulty Marxist reasoning, “steal” value from capitalists. (They don’t, of course. Contracts are knowingly agreed upon using imperfect knowledge. Even if the above scenario is true, which it often is, that is no foul play by either party. And vice versa.) So: worker theft is a fiction.

³The unlikely result of a subjective theory of value is that profit is not merely not evil but not made up: the world really does get richer, cheaper, and newer with the advent of new products and services. The world in 2025 isn’t some blunt redistribution of the world from 1025; the changes over that millennium cannot be classified solely as apportion or appropriation or expropriation by any given class against another; and the wealth of any given individual, at any given time, is not the necessary proof of a lack of wealth of any other individual. In fact—as I have also explained elsewhere—in a free market, the existence of wealth disparities is actually beneficial to the poor. Billionaires make us richer, not poorer.

But I want to dedicate this piece to points 4) and 5). The numbers—and the scaling of such numbers—themselves. (“The numbers, Mason. What do they mean?”) This obsession with “a billion”, a one with nine zeroes, three commas, ten digits, eight letters, is baffling. I touched on the phenomenon in the Merion West article:

“The very number one billion, many have argued, is so stupendously large, so unwieldy and immoderate, that no honest person should ever wish to possess it. Nor, they go on to add, should they be able to. This “argument from enormity” is often illustrated with the aid of an intuition pump: some visualisation, usually of the number of seconds or years it would take to naturally accrue such a figure. Imagine, for example, you were to earn $1 a second, every second, starting today. That’s $3600 an hour, $86,000 a day and over $600,000 a week—the real life salary, in fact, of Lionel Messi, Barcelona striker and highest paid sportsman alive. But even under this monumental payment plan, you wouldn’t achieve billionaire status until the year 2051, almost 32 years later.”

The scale of the thing, not the thing itself, is considered evil. The very word “enormity” embodies some implied mutation of what should be considered “normal” or indeed “normative” in modern society. And cancer is precisely the apposite metaphor in the minds of those disgusted by what they view as malignant: a growth in need of removal by surgery and destruction by autoclave.

But where does that leave the number? If there exists a moral quantity of wealth below which people can avoid damnation, then the assets themselves are not immoral, merely the amount. But what amount?

Most people can just about grasp the idea of a thousand individual things, the number of days in three years, the number of skittles in a jar at a village fete; and we believe that we have a handle on a million things until we learn that that is the number of days since the birth of Homer. But a billion? A trillion? (The number of days since the advent of oxygen.) What even comes after that? How can one person own a thing they cannot hope to hold in their mind, let alone in their hands?

This is, I think, where the enormity fallacy originates: a laced cocktail of points 3), 4), and 5) from my original list—plus a garnish of disgust in the face of the awesome. One part money to two parts numerals, shaken—not stirred—like a painting by Guy Buffet and expelled the following morning as a Progressive policy announcement. The entire it-would-take-this-many-years line of reasoning relies on yet more counting yet very little accounting for the truest theories of economics.

So, let’s take them one at a time. First:

Wealth does not equal money

Money is a representation of value, physical or digital, that fallibly approximates some measure of wealth. But money is merely that: a proxy. The meaningful difference between money and wealth is most evidenced by inflation: as more money is printed each individual bank note becomes less valuable because it represents a smaller proportion of the same fixed wealth. If any given wealth can be represented by one coin or 10,000 coins (the approximate exchange rate of the Polish Zloty and Iranian Rial), then the measure of that wealth is independent of those coins. Wealth does not equal money.

Quantifying wealth by numbers is misleading

For the reasons outlined above, the numbers themselves don’t really matter. At current exchange rates, for example, you only need to own $11,000 to own 1 billion Lebanese pounds. That means that one third of the US population are liquid billionaires and that 80 percent earn more than a billion a year. Those numbers that once seemed so ineffable now equate to a 2016 Chrysler Pacifica; and those people that once seemed so unethical now equate to your grandmother. It is purchasing power (the ability to leverage products, services, or otherwise influence the world) not bank statements (the numerical representation of that ability) that measures wealth. Quantifying wealth by numbers is misleading.

Criticising wealth by numbers is harmful

The moral effect of numerical theories is simple: to frame wealth as money, and money as counting, and counting as slow, painful, immortalised toil; and to simultaneously frame the wealthy as those who have counted too far, far beyond dignity, grandeur, solemnity, and awfulness—who have committed some unwritten epistemic trespassing (“We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.”) the punishment for which is spiritual disembowelment by eldritch leviathans—is designed solely and endlessly to demonise wealth.

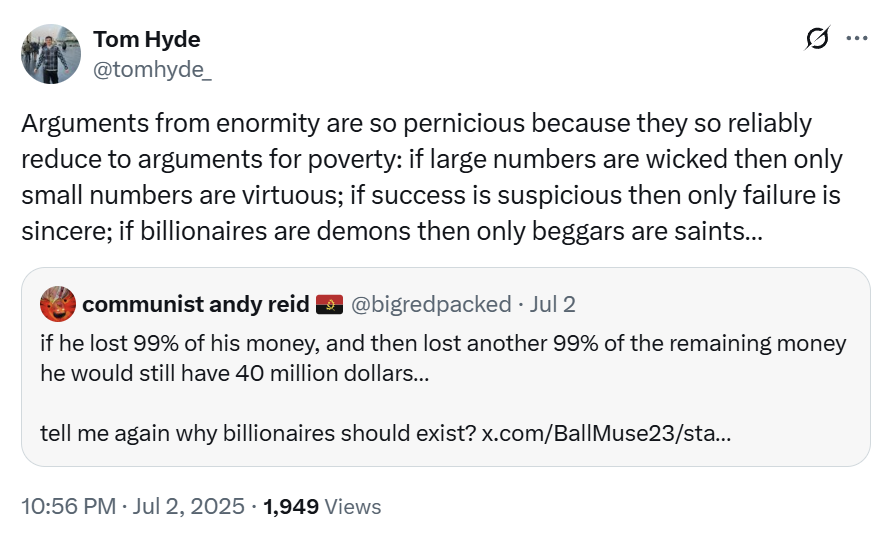

And, as I wrote on twitter/X, much worse than that: to romanticise poverty:

But as we have seen, the numbers are fictions. Elon Musk, at time of writing, has a net worth of $496 billion. Arguments from enormity might conjure some thought experiment about the number of hedgehogs from here to Andromeda. But he is, in reality, just one man—just one—with the ability to leverage rockets, Teslas, tunnels, Twitters, Groks, and more; he is no more invading the unthinkable than grandma and her Pacifica; and he is not one single hedgehog closer to the truly unthinkable distance between everyone and our truly infinite potential. As I wrote in Merion West:

“Indeed, many moral and economic truths follow only from an understanding of infinities: the mind-bending properties of numbers without end. One such property is encapsulated in the title of [David] Deutsch’s book [The Beginning of Infinity]: that no matter how far we are, no matter how large we get, we are always and forever at the beginning. There is no half-way nor nearly there, no just right nor too much. It is on this basis that arguments from enormity fail, and that appeals to poverty triumph. We will forever remain poorer than our next step forward.”

The enormous fallacy is, in reality, a minor mistake. It is a simple miscalibration, a framing error resulting from a universal campaign to minimise our confidence. Large numbers, when they are used, should be used to inspire, not subdue. One million, one billion, one trillion and the rest are most meaningful as measures of our continued success. They are monuments, not memorials; idols, not omens; and it is always worth remembering that they can always be greater.

But who’s counting?

Follow me on twitter/X @tomhyde_